Building Go Agents and Workflows on the Blades Architecture

What is an Agent?

Section titled “What is an Agent?”There is no unified, strict definition of Agent in the industry. Descriptions of Agents vary slightly among different vendors, open-source communities, and even academic papers. However, overall, an Agent typically refers to an intelligent system capable of long-term autonomous operation, possessing certain decision-making abilities, and able to call various external tools as needed by the task.

It can manifest as a program that “understands goals, makes judgments, and executes actions,” or it can be a traditional rule-based fixed-process robot.

In Blades, we collectively refer to these different forms as Agentic Systems. Although they all fall under the category of Agents, when designing the actual architecture, it is essential to distinguish between two core concepts: Workflow and Agent.

Workflow

Section titled “Workflow”Workflow leans more towards traditional software thinking: it relies on predefined execution steps to organize the calling relationships between LLMs and tools. All logical sequences are planned in advance and hardcoded into flowcharts or code.

Characteristics:

- The execution path is fixed and predictable

- The inputs, outputs, and conditional branches for each step are predetermined by the developer

- More suitable for tasks with standardized, stable, and decomposable business processes

- Easy to control boundaries, test, and audit

In a nutshell: The model follows the process, rather than the process adapting to the model.

The core value of an Agent lies in its “autonomy” and “adaptability.” It does not run according to a flowchart; instead, it uses the LLM as the “brain” to dynamically decide the next step based on the task objective and current state.

Typical capabilities of an Agent include:

- The LLM autonomously decides the execution steps, rather than relying on a preset process

- Capable of autonomously selecting, combining, or making multiple calls to external tools

- Possesses “memory” and “understanding” of the global task state during execution

- Dynamically changes strategy based on real-time feedback, rather than following fixed branches

- In some cases, it can run continuously, similar to a “service-type Agent”

Therefore, compared to a Workflow, an Agent is closer to an active executor rather than a passive process node.

In a nutshell: A Workflow is “the process controlling the model,” whereas an Agent is “the model controlling the process.”

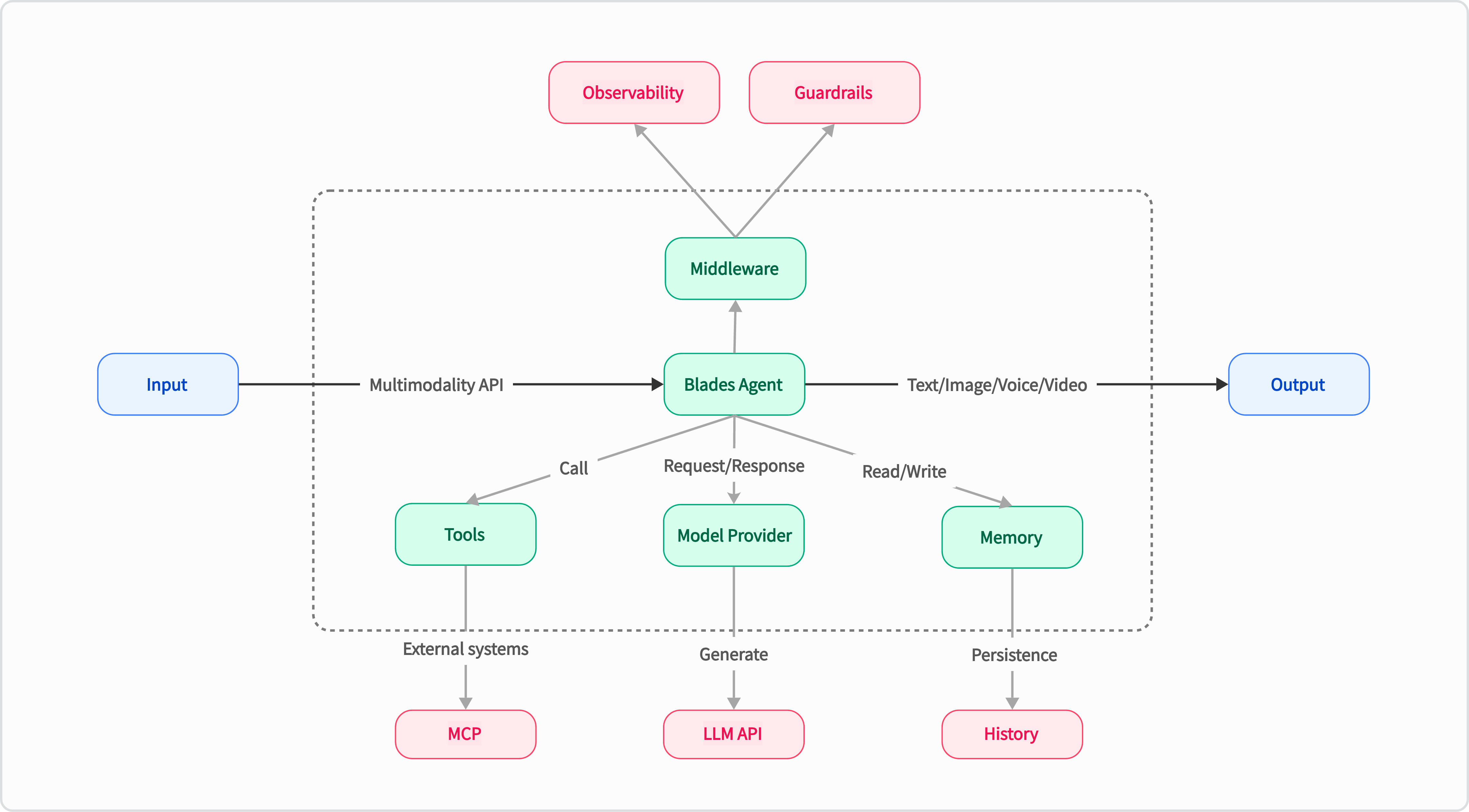

Building with Blades: Agent

Section titled “Building with Blades: Agent”Leveraging Go’s concise syntax and high concurrency features, Blades provides a flexible and extensible Agent architecture. Its design philosophy is to enable developers to easily extend Agent capabilities while maintaining high performance through unified interfaces and pluggable components. The overall architecture is as follows:

In Blades, you can create an Agent using blades.NewAgent. The Agent is the core component of the framework, primarily responsible for:

- Calling the LLM model

- Managing tools

- Executing prompts

- Controlling the entire task execution flow

Simultaneously, Blades provides an elegant and straightforward way to customize tools using tools.NewTool or tools.NewFunc, allowing the Agent to access external APIs, business logic, or computational capabilities.

Here is an example of a custom weather query tool:

// Define weather handling logicfunc weatherHandle(ctx context.Context, req WeatherReq) (WeatherRes, error) { return WeatherRes{Forecast: "Sunny, 25°C"}, nil}// Create a weather toolfunc createWeatherTool() (tools.Tool, error) { return tools.NewFunc( "get_weather", "Get the current weather for a given city", weatherHandle, )}Then build a smart assistant (Weather Agent) capable of calling the weather tool:

// Configure the model to call and its addressmodel := openai.NewModel("deepseek-chat", openai.Config{ BaseURL: "https://api.deepseek.com", APIKey: os.Getenv("YOUR_API_KEY"),})// Create a Weather Agentagent, err := blades.NewAgent( "Weather Agent", blades.WithModel(model), blades.WithInstruction("You are a helpful assistant that provides weather information."), blades.WithTools(createWeatherTool()),)if err != nil { log.Fatal(err)}// Query the weather information for Shanghaiinput := blades.UserMessage("What is the weather in Shanghai City?")runner := blades.NewRunner(agent)output, err := runner.Run(context.Background(), input)if err != nil { log.Fatal(err)}log.Println(output.Text())With Blades’ framework design, you can quickly build an Agent capable of both calling tools and making autonomous decisions with just a small amount of code.

Next, we will introduce several typical workflow patterns based on the Blades framework. Each design pattern is suitable for different business scenarios, ranging from the simplest linear flows to highly autonomous Agents. You can choose the appropriate design method according to your actual business needs.

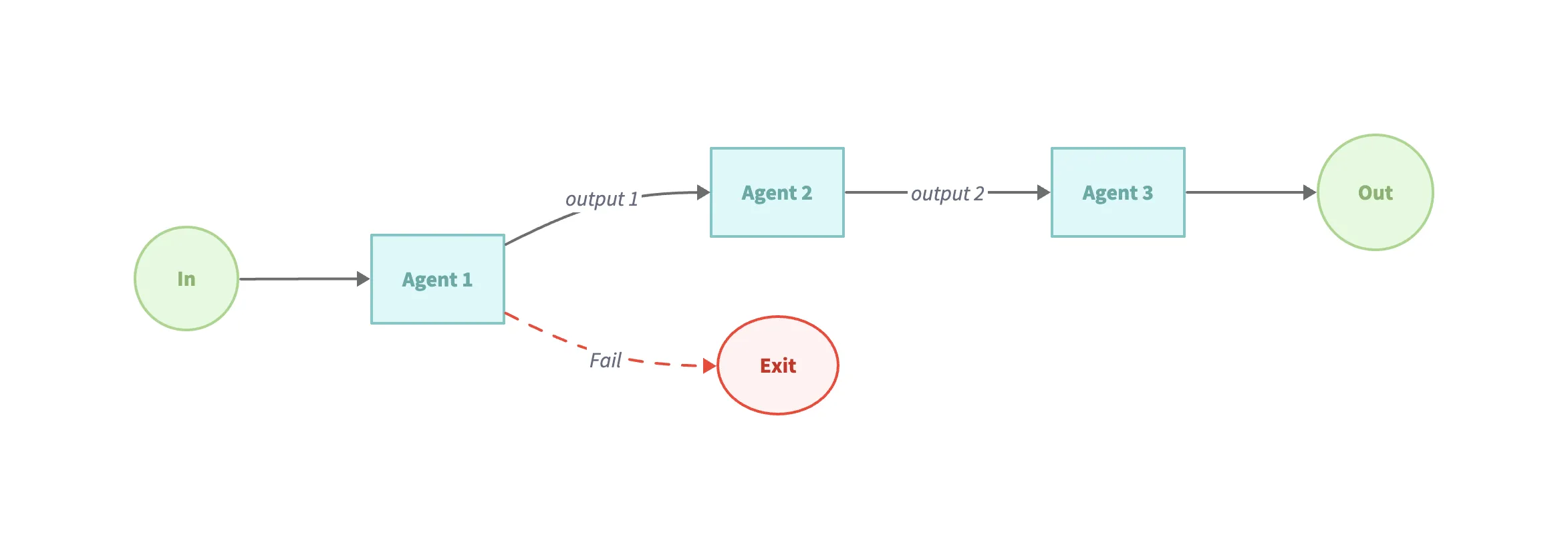

Pattern 1: Chain Workflow

Section titled “Pattern 1: Chain Workflow”This pattern embodies the principle of “breaking down complex tasks into simple steps.” Applicable scenarios:

- The task itself has clear, sequential steps.

- Willing to sacrifice a little latency for higher accuracy.

- Each step depends on the output of the previous step.

Example code (examples/workflow-sequential):

// Sequential workflow, executing agents according to the arranged ordersequentialAgent := flow.NewSequentialAgent(flow.SequentialConfig{ Name: "WritingReviewFlow", SubAgents: []blades.Agent{ writerAgent, reviewerAgent, },})Pattern 2: Parallelization Workflow

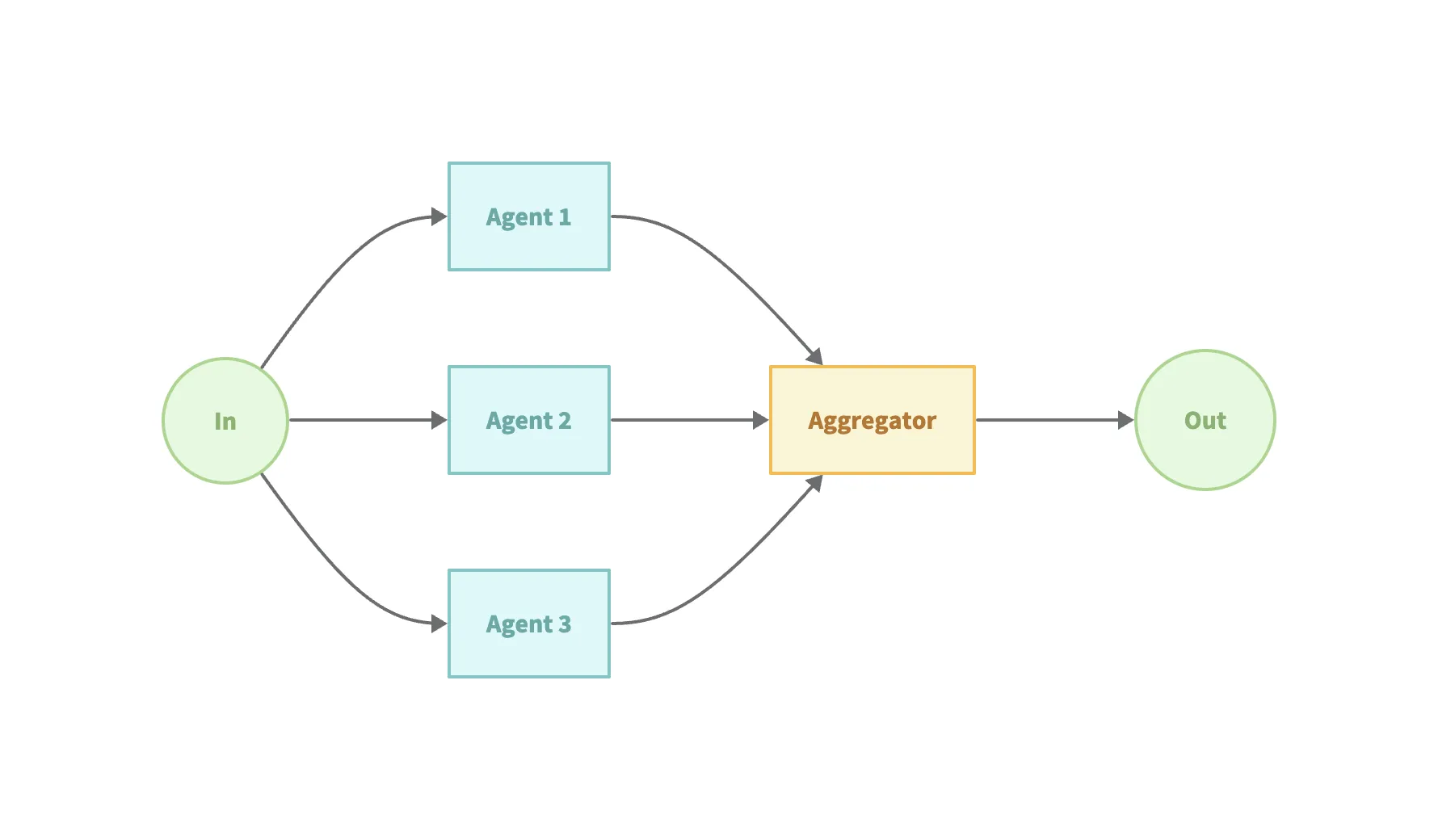

Section titled “Pattern 2: Parallelization Workflow”This pattern is used to have the LLM process multiple subtasks simultaneously and then aggregate the results.

Applicable scenarios:

- Need to process a large number of “similar but independent” items.

- The task requires multiple different perspectives.

- Time-sensitive and the task can be parallelized.

Example code (examples/workflow-parallel):

// Parallel workflow, storing generated results in the session state for reference by subsequent processesparallelAgent := flow.NewParallelAgent(flow.ParallelConfig{ Name: "EditorParallelAgent", Description: "Edits the drafted paragraph in parallel for grammar and style.", SubAgents: []blades.Agent{ editorAgent1, editorAgent2, },})// Define a sequential workflow, incorporating the parallel definitionsequentialAgent := flow.NewSequentialAgent(flow.SequentialConfig{ Name: "WritingSequenceAgent", Description: "Drafts, edits, and reviews a paragraph about climate change.", SubAgents: []blades.Agent{ writerAgent, parallelAgent, reviewerAgent, },})This pattern can significantly improve throughput, but be mindful of the resource consumption and complexity introduced by parallelism.

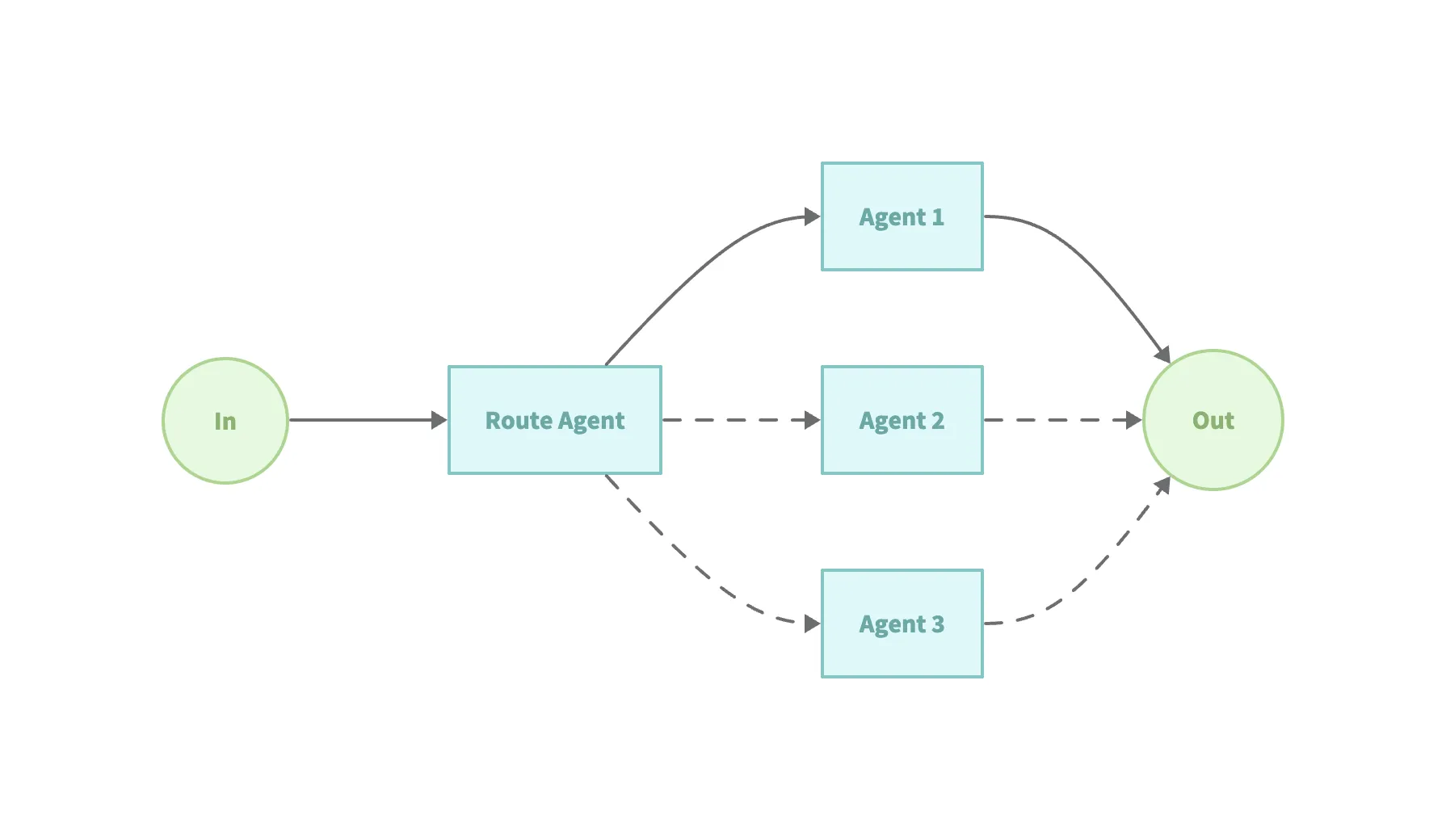

Pattern 3: Routing Workflow

Section titled “Pattern 3: Routing Workflow”This pattern uses the LLM to intelligently judge the input type and then dispatches it to different processing flows. Applicable scenarios:

- Multiple input categories with significant structural differences.

- Different input types require specialized processing flows.

- High classification accuracy is achievable.

Example code (examples/workflow-routing):

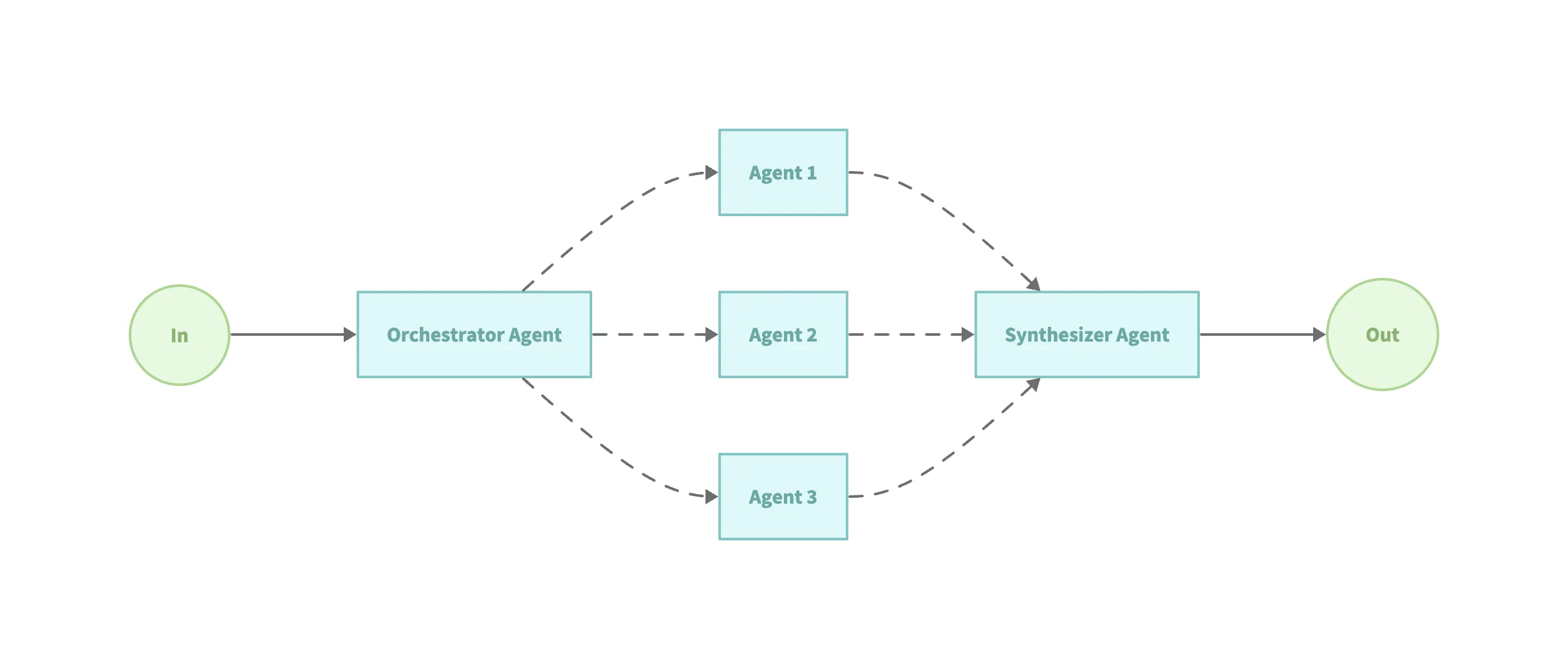

// Automatically selects the appropriate expert agent based on the Agent's descriptionagent, err := flow.NewRoutingAgent(flow.RoutingConfig{ Name: "TriageAgent", Description: "You determine which agent to use based on the user's homework question", Model: model, SubAgents: []blades.Agent{ mathTutorAgent, historyTutorAgent, },})Pattern 4: Orchestrator-Workers

Section titled “Pattern 4: Orchestrator-Workers”This pattern combines the “Agent” tendency: a central LLM acts as a task decomposer (orchestrator), and different “Workers” execute the subtasks.

Applicable scenarios:

- Cannot fully predict subtasks in advance.

- The task requires multiple perspectives or processing methods.

- Requires system adaptability and complex decision-making processes.

Example code (examples/workflow-orchestrator):

// Define translators via tools (Agent as a Tool)translatorWorkers := createTranslatorWorkers(model)// The orchestrator selects and executes the required toolsorchestratorAgent, err := blades.NewAgent( "orchestrator_agent", blades.WithInstruction(`You are a translation agent. You use the tools given to you to translate. If asked for multiple translations, you call the relevant tools in order. You never translate on your own, you always use the provided tools.`), blades.WithModel(model), blades.WithTools(translatorWorkers...),)// Synthesize the multiple generated resultssynthesizerAgent, err := blades.NewAgent( "synthesizer_agent", blades.WithInstruction("You inspect translations, correct them if needed, and produce a final concatenated response."), blades.WithModel(model),)Pattern 5: Evaluator-Optimizer

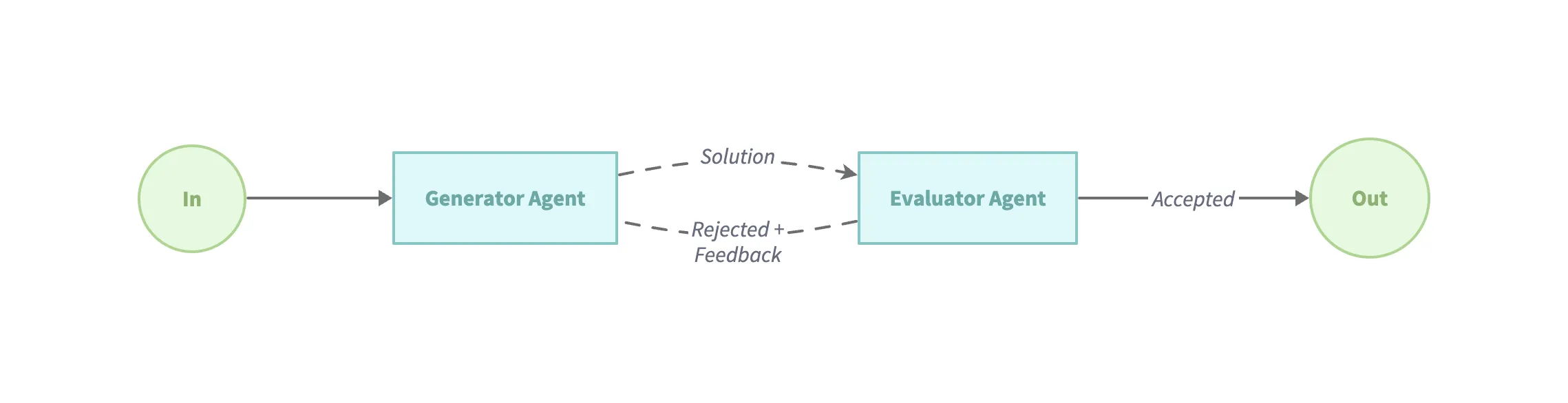

Section titled “Pattern 5: Evaluator-Optimizer”In this pattern, one model generates output, and another model evaluates that output and provides feedback, mimicking the human “write then revise” process. Applicable scenarios:

- There are clear, quantifiable evaluation criteria.

- Quality can be significantly improved through multiple rounds of “generate → evaluate → improve”.

- The task is suitable for iterative refinement.

Example code (examples/workflow-loop):

// Iterates multiple times by generating content and then evaluating the effectloopAgent := flow.NewLoopAgent(flow.LoopConfig{ Name: "WritingReviewFlow", Description: "An agent that loops between writing and reviewing until the draft is good.", MaxIterations: 3, Condition: func(ctx context.Context, output *blades.Message) (bool, error) { // Evaluate content effectiveness to determine whether to end the iteration return !strings.Contains(output.Text(), "The draft is good"), nil }, SubAgents: []blades.Agent{ writerAgent, reviewerAgent, },})Best Practices and Recommendations

Section titled “Best Practices and Recommendations”In business practice, whether for a single agent or a multi-agent architecture, engineering design often determines the final outcome more than model capability.

The following practical recommendations summarize the most critical principles from real projects and can serve as a reference when designing and implementing agents.

Start Simple

- Build a basic workflow first, then consider more complex agents.

- Use the simplest pattern that meets the requirements.

Design for Reliability

- Define clear error handling mechanisms.

- Strive to use type-safe responses.

- Add validation at every step.

Trade-offs

- Balance latency against accuracy.

- Evaluate the scenario before deciding on parallelism.